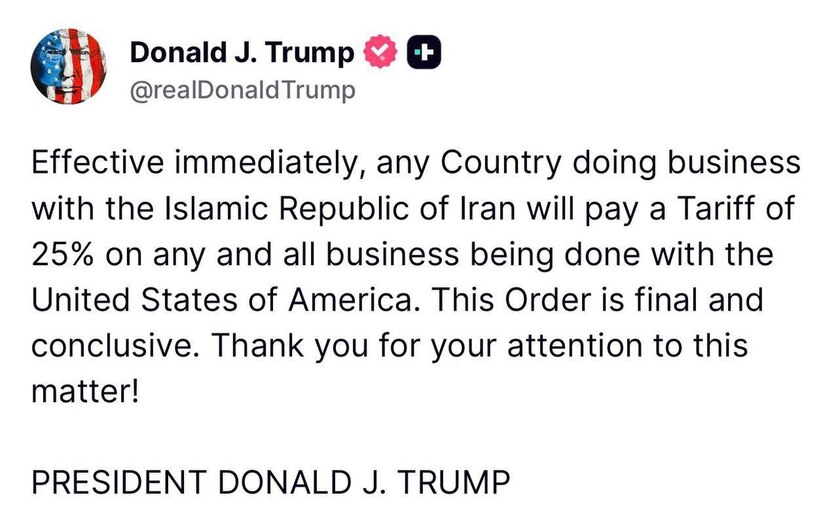

I simply can’t stay ahead of stupid. I finished this essay when Trump posted about Tarriffs. The only thing we need to do is just post stupidity in action.

Power Is Not Leadership

Powerful people make the same mistake over and over again: they confuse the ability to impose outcomes with the ability to lead.

They think volume is vision.

They think force is followership.

They are wrong.

Leadership is not domination.

It is the capacity to coordinate others through trust, consistency, and constraint — especially when you could get away with doing otherwise.

Power without restraint is like a weapon without a safety: impressive until pressure is applied — then catastrophic.

Force can compel behavior. Leadership cannot.

Leadership only works when others believe you will remain bound by the same rules tomorrow that you invoke today.

This distinction matters because when leaders abandon it, everything beneath them begins to decay.

What we are witnessing across institutions and nations is not merely aggressive rhetoric or hardline policy. It is a leadership vacuum — the erosion of self-restraint at the top and the quiet normalization of exception beneath it.

And leadership failure spreads.

A leader who treats rules as optional teaches everyone watching that rules are negotiable. A leader who substitutes threats for persuasion teaches institutions that compliance matters more than legitimacy. A leader who elevates personal conviction over shared norms teaches followers that loyalty outranks responsibility.

This is not ideology. It is the transmission of power without limits.

When a leader declares that law no longer binds them because of their personal morality, they are not asserting ethical clarity. They are declaring exemption. And exemption is the opposite of leadership. It signals that standards exist for others, but not for the person in charge.

That posture does not inspire confidence. It destroys it.

The clearest examples of effective leadership in the modern era are not found in moments of dominance, but in moments of restraint.

History is unambiguous once we stop confusing scale with authority.

Nelson Mandela emerged from prison with every justification to retaliate. He had the mandate, the numbers, and the moral high ground. He chose restraint instead — not as sentiment, but as strategy. By binding himself to reconciliation, he denied civil war its momentum. His authority came from refusing to use force when he could have.

Dag Hammarskjöld understood restraint as institutional discipline. He treated power as something to be limited, not exercised. Peacekeeping under his leadership was designed to prevent escalation, not impose outcomes. Neutrality, process, and self-constraint were his sources of legitimacy — and he paid for that commitment with his life.

B. R. Ambedkar practiced restraint through law. Drafting India’s constitution after colonial rule and mass violence, he rejected majoritarian revenge. Instead, he embedded limits, protections, and equality into the structure itself. His leadership was quiet, durable, and deliberately anti-dominant.

These leaders shared one understanding: leadership is not the ability to impose outcomes, but the discipline to limit oneself.

Restraint was not their weakness. It was the source of their authority.

Leadership works like this because people — and nations — follow those they believe will remain steady when the rules become inconvenient.

Remove that, and fear replaces respect.

This is why leadership failures cascade.

When leaders negotiate through threats, they may extract compliance — but they do not earn commitment. When leaders treat relationships transactionally, partners become temporary deals rather than allies. When leaders frame every interaction as leverage, everyone involved learns to hedge, defect, or wait them out.

Transactional leadership is a contradiction in terms.

A transaction can buy obedience. It cannot create loyalty. You cannot bargain people into shared purpose. Stability built on coercion always demands escalation.

That is not a moral critique. It is structural.

And when transactional logic governs leadership, legitimacy becomes the first casualty.

We have seen this dynamic play out repeatedly, not just between states, but within them.

When a police officer kneels on a man’s neck for nearly ten minutes in full view of the public, the act is not only violence. It is instruction. It tells every observer — uniformed or not — that rules bend for those with power and collapse for those without. That is not a localized failure. It is leadership collapse made visible.

Leadership models. It does not fail quietly.

This is why belligerence is not a sign of strength.

It is a symptom of insecurity.

Leaders resort to force when persuasion fails. They escalate when credibility collapses. They threaten when they no longer believe their word is sufficient.

History is unambiguous here. Abraham Lincoln held a fractured union together not through domination, but through consistency, restraint, and an unwavering commitment to process under pressure. He understood something modern leaders often forget: authority is sustained by self-restraint, not spectacle.

Empires and institutions do not unravel because leaders lack power. They unravel because leaders confuse intimidation for authority and motion for direction. Systems held together by coercion exhaust themselves. Authority that depends on fear must constantly prove itself.

Eventually, it outruns its own capacity.

None of this means collapse is inevitable. Nations do not disappear because leadership fails. People endure. Societies reorganize. What changes is who is trusted to lead.

But leadership, once lost, is difficult to recover.

The world does not need louder leaders.

It needs steadier ones — leaders who understand that legitimacy is not claimed, but earned; that authority is not imposed, but maintained; and that power exercised without restraint is not leadership at all.

Belligerence may look decisive.

It may feel strong.

But it is what leaders reach for when they have run out of authority and are bluffing their way through the wreckage.

It is not a governing style.

It is a failure mode.

And the most dangerous part is this:

We have started calling it normal.